Harry Geels: Monetary union increasingly based on Latin principles

Harry Geels: Monetary union increasingly based on Latin principles

By Harry Geels

The EU has relaxed its budgetary rules in the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). The most important relaxation concerns the abolition of the 5% rule, which means that countries with too much debt have to make cuts less quickly. This will not do any good to the strength of the euro in the long term.

After lengthy negotiations, the EU has relaxed its fiscal rules from the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). The agreement, concluded between MEPs and then EU President Belgium, focuses on tackling high national debts and budget deficits from 2024-2025. At first glance, the original demands from the SGP (maximum government debt of 60% of GDP and a government deficit of a maximum of 3% per year) appear to remain in place. Nevertheless, there are a number of important relaxations.

Firstly, the '1/20 rule', the mandatory 5% debt reduction for too much debt, will no longer apply. 'Anyone who has a debt higher than 90% of GDP reduces it by 1% annually. Anyone who has a debt between 60% and 90% reduces it by 0.5% per year. And deficits above 3% must be reduced to 1.5%', as explained in the FD. Furthermore, there appears to be room for negotiation, because countries with exceedances and deficits must make a plan on how they will achieve the standards and at the same time strengthen the economy.

More top-down interference and open ends

'Member States get four years for their national plan. That can be stretched to seven years if countries invest more in useful matters such as climate and inequality. The higher the debts, the more closely Member States must listen to Brussels advice on maximum spending,' according to the same article. EU countries will receive another relaxation if they invest in social projects together with Brussels through co-financing. The European Parliament will then fully exempt them from those investments in the calculation of the net expenditure ceiling.

Brussels' power thus appears to become more directive, while the SGP had clearer and more objective criteria. It is also a prelude to more joint financing, as was already done with the corona bonds, which at the time were a breach of contract and would be one-off. Of course, the SGP has been a wash for years. Northern euro countries have also not always complied. But making the treaty more flexible is not the right way to go. The question is also whether countries will be able to meet them with the new criteria.

Anyway 'mission impossible'

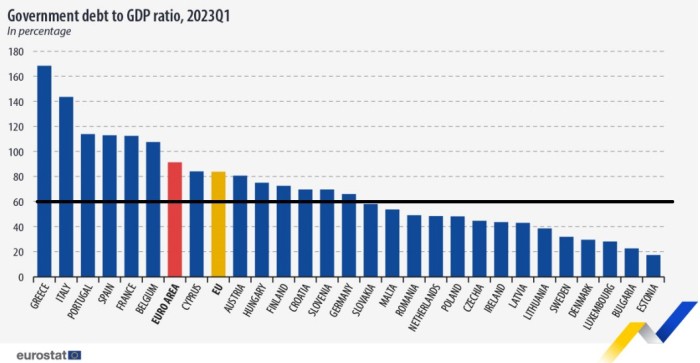

The question is whether Greece and Italy in particular will follow the new pact. Greece has a public debt of more than 160% of GDP. With the new minimum 1% reduction per year, it could take a hundred years before Greece meets the 60% criterion. In addition, since corona and the war in Ukraine, financial morale in many euro countries has been deteriorating. Where countries such as Greece and Italy should have been making heavy cuts for years, expenditure is difficult to get under control.

Figure 1

There is an even deeper cause for the mission impossible, especially for the southern countries, to meet the criteria, namely the flaws in the Eurosystem: one interest rate and one exchange rate do not work if the economies differ too much in terms of culture and dynamics. The euro is too expensive for weak countries, which inhibits exports, and it is too cheap for strong countries, which causes them to export a lot. And as for the policy interest rate: it is too low for well-functioning economies and too high for less well-functioning economies.

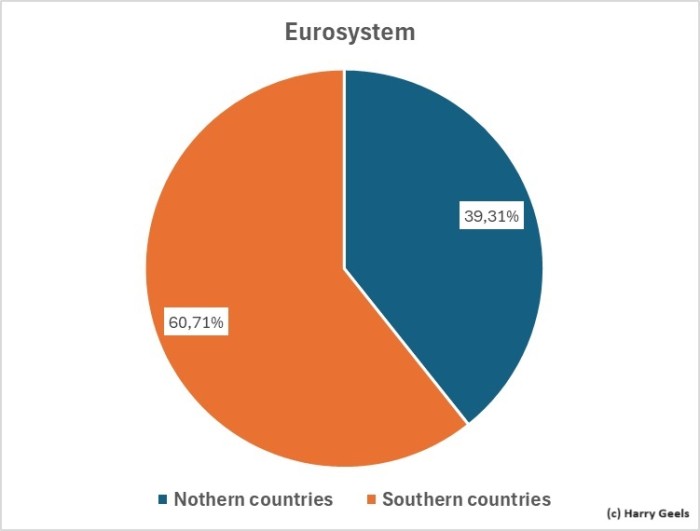

Figure 2

Hard monetary union does not exist (anymore)

Countries such as the Netherlands and Germany have built their wealth over the decades in part through a strong currency, which ensured that our open economy could import cheaply, go on holiday abroad cheaply and help keep inflation under control. Of course, the guilder and the German mark were a challenge for exports, but that was compensated by the aforementioned cheaper imports and smart innovation, such as increasing production capacity and making good quality products. A strong currency simply has a disciplinary effect.

Due to the strict monetary (and usually fiscal) policy, the Northern countries also generally had lower interest rates than countries that were less strict in their approach. Consumers and companies could thus finance themselves more cheaply than elsewhere in the world. That policy no longer exists. The ECB pursues a much looser monetary policy, tailored to its weakest brothers, with the most grotesque form being Mario Draghi's negative interest rate policy, which forced savers and pensioners to pay for the euro's rescue.

Power lies in the south

The Netherlands should never have started with the euro. Firstly, because the eurozone did not meet the conditions for an Optimal Currency Area when it was introduced. Secondly, because there is (and was) no balance between the northern countries, with generally tighter monetary policies, and the southern countries, with generally looser monetary policies. To put it more precisely: the Netherlands should never have participated in the eurozone with Italy and Greece, which did not meet the SGP criteria at the time and still do not and never will.

Figure 3

Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/orga/capital/html/index.en.html

Thirdly, because, as Margaret Thatcher so eloquently predicted in her ('must-see') farewell speech as Prime Minister, the ECB has increasingly become involved in politics, putting democracy in the individual euro countries under pressure. The ECB is now involved in all kinds of social matters, such as the climate and equality. And now there is more interference from all kinds of EU bodies in the assessment of plans, in the application of the more flexible SGP criteria. Politics and official bureaucracy will thus become even more involved in the criteria that determine the strength of the euro.

'What a mess!' In this way, the euro will never become a strong currency, or a reserve currency with political strength. To save the euro or not – and how?

This article contains a personal opinion from Harry Geels