Craig MacDonald (ASI): ESGP investing in Emerging Market Debt

Craig MacDonald (ASI): ESGP investing in Emerging Market Debt

ESG is a useful tool for investing in EMD, but Craig MacDonald, Global Head of Fixed Income at Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI), goes one step further: ‘When used as part of a wider investment process, an ESGP framework may help to explain differences in sovereign credit spreads.’ Financial Investigator spoke with him.

Why do you think an ESG approach is well suited for investing in sovereign debt of emerging markets?

‘As we all know, a country’s creditworthiness is fundamentally dependent on its competitiveness and its ability to sustain economic growth over the long term. To assess this, investors traditionally look at a range of macroeconomic variables, including public debt, inflation, fiscal deficits and current account balances.

Again, as we know, the ability to sustain economic growth depends on socio-economic factors. These include the level of inequalities, education, health systems, the quality of infrastructure and the environment, as well as resource constraints.

Institutional weaknesses and social issues can amplify macroeconomic fragilities. This is why we believe that Environmental, Social, Governance and Political (ESGP) factors are useful in assessing sovereign creditworthiness in a more holistic manner. At our organisation, we’ve developed our proprietary ESGP framework for EMD.’

Can you explain this in more detail?

‘We developed this framework because we believe ESGP factors could act as either catalysts or socio-economic factors. They are also often intertwined and mutually reinforcing. Poor education and health systems can increase inequality and hamper economic growth, which in time can threaten political stability. Unwillingness or difficulty in addressing environmental and social challenges can be a major impediment to long-term growth. This could hurt competitiveness and affect a country’s ability to repay debt. By contrast, countries with good ESGP performance should be more resilient to shocks, such as natural disasters, financial crises or geopolitical instability.’

How does that look in practice?

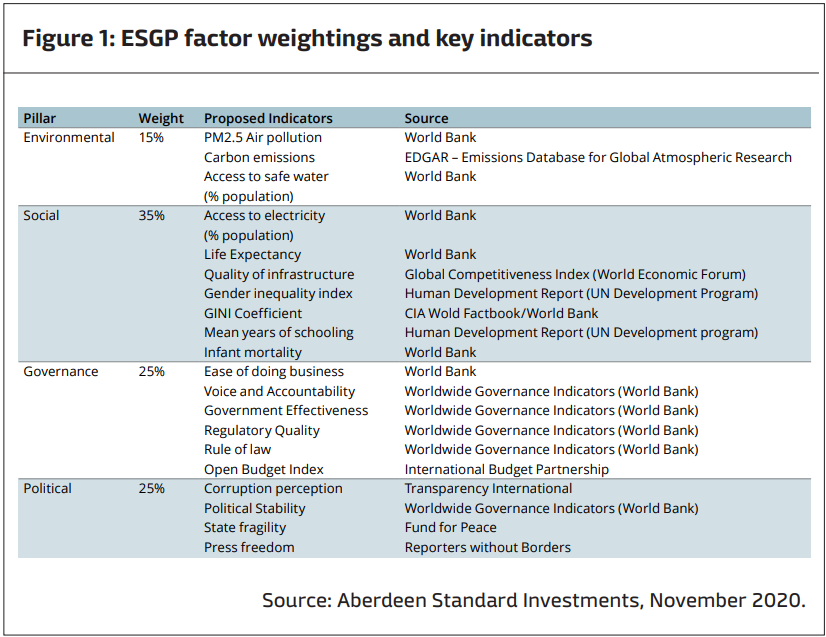

‘Our ESGP framework covers 91 countries from the EM universe. The first consideration is indicator selection, which we have tailored specifically to emerging markets. For instance, we look for indicators of institutional stability and governance that have traditionally proven necessary for sustainable development. In total, we use 20 indicators, from which we derive an ESGP score for each country1.’

The political dimension is an interesting aspect. What kind of factors do you measure?

‘I agree. So, for us, political indicators assess government institutions in a dynamic way, looking at the factors that could pose a threat to national security and democracy. Here, we look at the prevalence of corruption in the public sector as it is perceived by citizens and factors that promote the outbreak of violence and conflicts.

Politics is a key aspect for investors as it drives economic policy and growth in emerging markets much more significantly than in developed economies. Along with transparent policymaking and sustainable growth comes a greater likelihood of debt repayment.’

In what way do you use that information?

‘For each indicator, we calculate Z-scores, which signal where each country lies relative to the average of that particular indicator.

The Z-scores are then averaged within each of the four dimensions, resulting in a score for each pillar. Finally, our overall ESGP score is calculated as a weighted average of each pillar’s score, with weights as follows: environmental 15%, social 35%, governance 25% and political 25%. Combined, the political and governance pillars account for 50% of the overall ESGP score. We believe that these two factors have the greatest impact on a country’s ability to sustain its growth and repay its debt.

Additionally, political and governance factors can be key catalysts for or impediments to the improvement of socioeconomic and environmental factors. We have given a bigger weight to the social pillar (35%), given the number of sub-themes taken into account (inclusive growth, infrastructure, health and education) and the increased importance of these factors for long-term growth in EM countries, compared to their developed market counterparts.

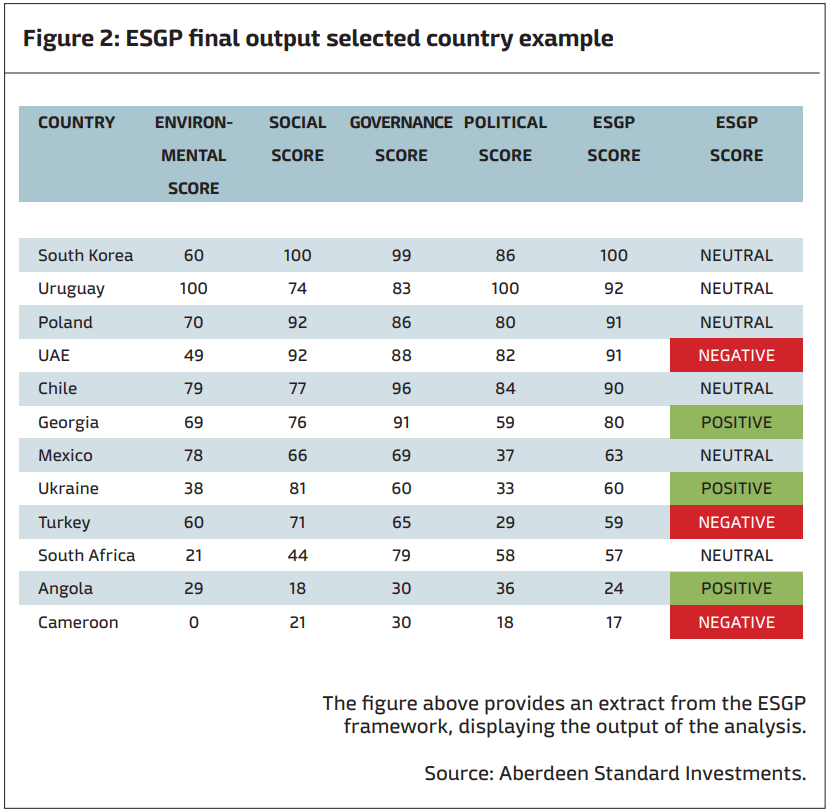

We then normalise the ESGP scores on a scale from 0 to 100, with the worst-performing country receiving a score of 0 and the best-performing country scoring 100, while preserving the distribution of deviations from the mean.’

What does all this mean?

‘The primary objective of the ESGP framework is to invest in sovereign bonds with attractive credit fundamentals, good growth prospects and, crucially, attractive pricing relative to the risks. The key benefit of this approach in this context is its potential to give a more complete and refined picture of the risk side.

As active investors, our aim is to find instances where credit fundamentals and risks may be mispriced. As shown in Figure 2, we place great emphasis on the ‘direction of travel’ of ESG factors and scores, as such dynamics are more likely to be mispriced by the market. Another key advantage of a forward-looking emphasis is the reduced risk of excessively penalising (and therefore under-allocating) to less developed countries. Their static (backward-looking) ESG scores might be low, but their direction of travel may be clearly positive. Conversely, the reverse risk of overallocating to developed countries with high scores but unfavourable dynamics might also be lessened.’

Any final thoughts?

‘We believe an ESGP approach is well suited to EM sovereign debt investing. As we’ve hopefully shown, our in-house proprietary framework helps us integrate ESGP factors in our research process in a systematic manner. By doing so, we believe we complement our existing research and gain a more complete picture of long-term EM credit risk. Ultimately, we believe this supports better and more sustainable investment outcomes.’

1 Measurement problems can affect the reliability of aggregated indicators of institutional quality and should be taken into account when assessing institutional differences across countries. For an in-depth discussion of those issues, please refer to: “Measuring Governance”, OECD Policy Brief No. 39 by Charles P. Oman and Christiane Arndt (OECD 2010). Therefore, inferences about small changes and differences in indicators across countries should be taken with caution.