Harry Geels: The disastrous path of homeland economics

This column was originally written in Dutch. This is an English translation.

By Harry Geels

Since last week we have a new economic word: 'homeland economics', an economy that is strongly influenced by increasing protectionist government policy, which also puts pressure on free markets. An alarming trend, as The Economist rightly notes. There may be a better alternative to homeland economics.

It cannot be a coincidence that, in the 300th anniversary of the birth of the Scot Adam Smith, who is seen as the founder of economic science, The Economist published a large dossier on homeland economics last week, entitled: 'Are free markets history?' and with the subtitle: 'Governments are jettisoning the principles that made the world rich.' Homeland economics is 'a protectionist ideology driven by many subsidies and interventions that is managed by an ambitious state'.

There are four reasons why homeland economics is emerging now and three reasons why it will not work. Then the question remains: 'What next?

Four frequently heard arguments for homeland economics

The supporters of homeland economics broadly rely on four arguments. The first emerged during the COVID-19 crisis, when lockdowns led to problems in supply chains. The idea took hold that it was better that countries, or closely related regions, should operate economically self-sufficiently, also with regard to the extraction of raw materials. When a major discovery of rare metals was made in Sweden at the beginning of this year, reporting on this was grotesquely orchestrated by the EU.

The second reason why we are in economic retreat is the big bad outside world. The US sees China as an economic threat and is starting to include Europe in this view. Furthermore, Russia has of course become a major warlike enemy who, at least if we can believe the reports, tries to influence our opinion through media trolls. Our personal data would also no longer be safe. That is why they should actually be stored locally or in the EU.

The energy transition is the third reason. The idea has arisen that the markets have failed and that the government must take charge of the transition. Because each major region – China, Europe and the US – has its own ambition levels, they want to do this in their own way, whereby the old industrial policy – promoting their own companies with subsidies – is also revived. Fourth, inequality and the sharp rise in prices, also allegedly caused by free markets, must be tackled.

Three reasons why homeland economics won't work

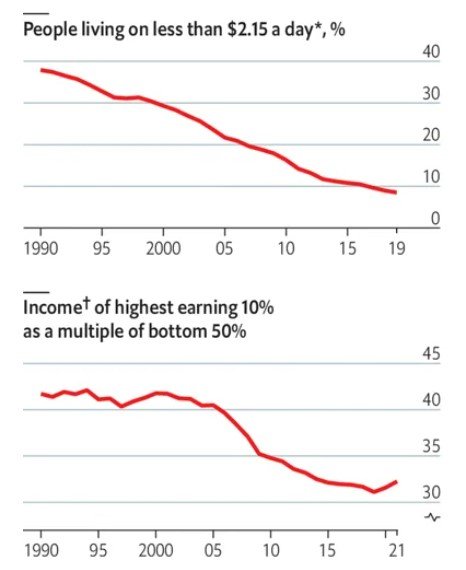

The Economist calls homeland economics an alarming trend. The business magazine shows that neo-liberalism 2.0 (Reagonomics, started in the early 1980s) has brought much economic prosperity to the world: the number of people living below the poverty line has fallen. The same applies to the ratio of the richest 10% versus the bottom 50%. However, problems have also arisen: the top 1% have become enormously rich, growth is reaching planetary limits and oligopolies are penalizing consumers.

Figure: 1 Economic prosperity through neo-liberalism 2.0

Source: The Economist

The first reason why homeland economics will not work is that this ideology misanalyses the current problems. The problem is not that neo-liberalism 2.0 is failing. The problem is that the system has gone crazy and has deviated too much from the original good principles of capitalism. A harmful form of 'corporate welfare state' has emerged, in which top people are rewarded too exorbitantly and too many tax avoidance routes are sought. A better solution is to restore the original neo-liberalism 2.0.

The second reason is the role of the government. We know from the past that the state does not solve problems more efficiently than the business community. In short, Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman explains in a minute and a half why this is the case. According to The Economist, in homeland economics we will overburden the state with unattainable responsibilities. Third, an inefficient government will frustrate the rapid and necessary social and technological changes.

What now?

As The Economist puts it, homeland economics will not be stopped anytime soon: 'People simply like to spend other people's money.' Or, as Professor Lex Hooguin recently said in an interview with Financial Investigator: 'People, especially intellectuals (including opinion makers), prefer to believe in social engineering rather than in the invisible hand of the free market. People probably also need something to hold on to, a Father State that will build Utopia for them.'

A completely different school of thought is that of the aforementioned Adam Smith, who described the concept of the invisible hand of the free market as a guideline for our prosperity in his magnus opus The Wealth of Nations. What many people are less aware of is that Smith was actually a philosopher, who provides the ethical, philosophical, psychological and methodological underpinnings of his economic principles in another (more readable) book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Smith argues that excessive concentration of wealth is not a good thing, that fair competition is good when wages are rising, and that taxes are necessary. He campaigned against large concentrations of power such as that of the East India Company, which allegedly used an 'extractive' form of capitalism. Smith also spoke in his Wealth of Nations of a 'steady state economy', in which growth in itself is not the goal, but in which a balance must be found between population growth and economic growth. Finally, the polluter must pay.

A more ethical-philosophical solution to the problems in the current system, as Smith developed before the Industrial Revolution, is a better route than the concept of homeland economics, which is mainly based on fallacies. Previously I reviewed Francis Fukuyama's book 'Liberalism and its discontents', which describes seven principles for a better liberal society. One of these, surprisingly enough, was also a philosophical one: that of Stoic moderation. This may be a better alternative than homeland economics.

This article contains a personal opinion from Harry Geels