abrdn: The Fed kills the cycle

abrdn: The Fed kills the cycle

The global economy is facing multiple headwinds, which in our new baseline scenario likely ends in recession. China is contracting as a result of its zero-Covid strategy, although growth should rebound later this year. Russia is in a sharp recession as a result of Western sanctions, even if the depth isn’t as bad as initially expected. And in Europe, the energy price spike is driving a rapid terms of trade deterioration, which will squeeze real incomes and crimp consumption.

However, the biggest challenge lies in the US. The inflation overshoot likely requires a significant rise in US unemployment to be brought under control. Our baseline envisages further sharp interest rate hikes and tighter financial conditions causing a recession to bring this about. In turn, a contraction in the world’s largest economy would have large negative global growth spill overs.

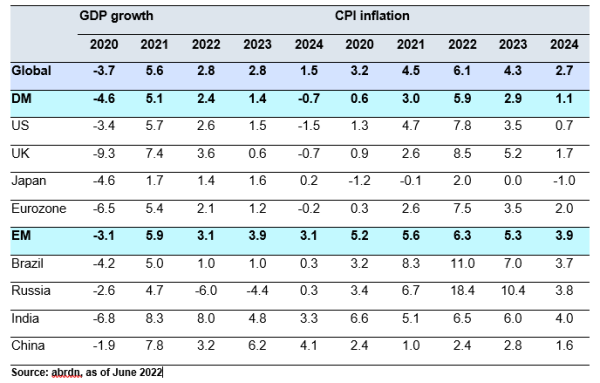

Global economic forecast summary

The “r word”

The “r word” is the talk of financial markets, but it is important to distinguish the varying sources, geographies, and time horizons of recession risk in the global economy.

Two of the big economies are already in contraction, albeit temporarily so. China’s zero-covid strategy is unsustainable and we expect it to be dropped after the 20th Congress in Q4. In the meantime, strict lockdowns in Shanghai have caused a short, sharp fall in Chinese real GDP of about 2% q/q in Q2. Chinese growth will rebound with the Shanghai lockdown now being eased, but the risk of further lockdowns remains until the zero-Covid policy is abandoned. China’s 2022 growth target is now unattainable, and this is reflected in our subdued forecast profile for the country.

Russia-Ukraine effects

Meanwhile, Western sanctions are causing a sharp contraction in Russia, although the size of the fall in GDP should be at the lower end of estimates. Russian energy exports have held up amid carve-outs, while the rouble has rebounded, allowing inflation and interest rates to fall. Nevertheless, we estimate a peak-to-trough contraction of 14%, equating to -6% annual growth in 2022. Any recovery will be weak amid ongoing sanctions, with our estimate of Russia’s annual potential growth now only 0.25%.

Moreover, our updated Russia-Ukraine scenarios envisage a prolonged conflict. This is characterised by continued fighting in the Donbas, with Russia failing to take fresh territory but Ukraine also struggling to force Russia to abandon its invasion. Critically for the global economy, this means continued sanctions, with an embargo on European imports of Russian oil imminent, and a rapid phase out of Russian gas underway.

Indeed, the next source of global recession risk is from the war-induced energy price shock,, which is most problematic for the Eurozone and the UK over 2022-23. Europe is a net energy importer and particularly reliant on Russian gas, causing a rapid deterioration in the terms of trade and a big squeeze on household real incomes. This is likely to cause a small contraction in European growth later this year, even if a technical recession is avoided. But should Russian gas imports be severed in one fell swoop – either due to an EU embargo or Russia cutting supply – then recession in Europe would be virtually guaranteed.

Finally, and most importantly, the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) interest rate hikes (and to a lesser extent hikes in the UK, Eurozone, Canada, and Australia) in response to very high inflation will mean policy exerts an increasing economic drag. The single most likely outcome is that taking interest rates rapidly above equilibrium will tip the US economy into recession in late 2023, and that this in turn would generate a global recession on our definition.

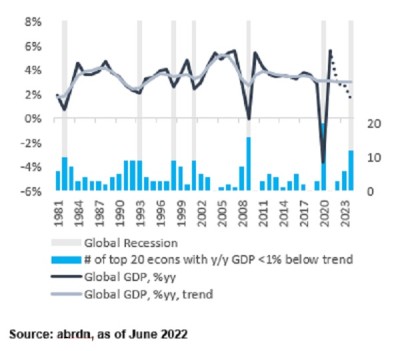

Our baseline GDP forecasts meet our preferred definition of global recession in 2024

After all, historical comparisons suggest engineering a soft landing will be difficult. In the major developed market (DM) economies, hiking cycles that don’t lead to recession are the exception, not the norm. Soft landings require residual labour market slack, wage and price pressures that are more moderate than now and borrowing levels that are below long-term trends. The first two of these conditions aren’t met today, meaning central banks are probably too far behind the curve to avoid a hard landing.

Nor should investors be reassured by the current strength of the data flow in many economies, because demand side strength only heightens imbalances and the size of rate hikes that ultimately trigger recession. In any case, there are signs of weakening activity in interest rate-sensitive sectors such as the US housing market, which may be straws in the wind for a wider downturn.

Timing and size of the coming recession

The timing and size of the coming recession is uncertain. Because we are primarily concerned about a policy tightening-driven downturn, the long and variable lags of monetary policy need to be allowed to work through the economy. We think this makes late 2023 into 2024 the most likely period of the global recession.

Meanwhile, recent experiences such as the Covid shock or Global Financial Crisis are poor benchmarks for the size of the recession because of the uniqueness of these periods. Instead, we expect the recession to resemble the business cycle downturns of the 1980s and ’90s. Nevertheless, that still means a 2% peak-to-trough fall in the US, which we think is the size of contraction needed to raise US unemployment sufficiently to bring inflation back to target. Many DM economies where trade and financial links with the US are significant, such as Canada, the UK, the Eurozone, Japan and South Korea, in turn experience 0.5-1.5% peak-to-trough contractions in our new baseline.

We also expect a meaningful slowdown in higher-growth emerging market (EM) economies, albeit the aggregate pass-through is smaller than into DM. Linkages with the US vary widely across EMs, but past US recessions have dragged on EM growth via the trade and financial channels. An economy like Mexico is at one end of the spectrum and likely to experience strong negative spillovers, while China will be much more insulated given its closed capital account and ability to run counter cyclical monetary policy.

Global inflation outlook

Turning to the global inflation outlook, headline rates should peak in Q3 this year and moderate as energy base effects drop out and supply chain disruptions slowly ease. However, the risks around this are skewed to the upside if energy prices rise further or China’s zero-Covid strategy means fresh disruption at major ports and manufacturing hubs.

But our biggest concern is sticky core inflation generated by tight labour markets. Our baseline judgement is that only policy rates above neutral and a recession that raises unemployment can tame this inflationary pressure. The size of recessions we are forecasting should bring core inflation back towards target rates by 2024.

The outlook for monetary policy is complicated by a recession entering our forecast horizon. We expect further sharp rate rise between now and mid-2023, to a peak of 3.375% in the case of the Fed, which is above our assessment of the neutral rate and precisely what generates the recession. But as the pending recession becomes more apparent in the data, we then forecast the start of a cutting cycle in 2024. Indeed, we think policy rates will return to around zero by the end of our forecast horizon, consistent with research showing lower bound episodes will be much more frequent in the future.

Balance of risks skewed to the upside

Importantly, while a US and global recession is the single most likely scenario, we think the balance of risks around this downbeat baseline is skewed strongly to the upside.

For a start, there is still a narrow path for monetary policy tightening to bring inflation under control, but without generating widespread recessions. But this “Fed walks the tightrope” scenario requires a lot to go right. Headline inflation has to moderate quickly as energy base effects drop out and supply disruptions unblock, while labour force participation rates need to rise to cool wage growth and without a big increase in unemployment. This scenario, which still involves a meaningful slowdown, resembles our previous baseline and the prevailing consensus view, which we now think is overly complacent.

Two other upsides we take seriously are a “supply side recovery” in which inflation moderates without a big slowdown in growth thanks to supply expansion, and a “rapid savings rundown” that sees households and businesses spend accumulated savings to more than offset the cost of living squeeze, although this would eventually need to be reined in with tighter policy.

But we continue to see risks of further energy price shocks, say if Russian gas exports to Europe are turned off imminently, leading to a “stagflation” scenario. This wouldn’t lead to a global recession because the US and China would be less effected, but would still involve weak growth and very high inflation. We are also concerned about imbalances in China’s property sector, motivating our “China stress and slowdown” scenario, which would likely cross the threshold of global recession even if it was marginally less severe than our baseline. In fact, the only scenario worse than our baseline is “total vaccine escape”, to which we continue to assign a small probability.

And finally…

All this means that, even with a global recession being our new baseline modal scenario, the weighted mean across all our scenarios actually avoids a global recession. This is an unusual risk distribution, but one which reflects the nature of the uncertainties in the outlook.