Aberdeen Standard Investments: What does the pandemic mean for long-term investors?

CRAIG MACKENZIE, HEAD OF STRATEGIC ASSET ALLOCATION, GLOBAL STRATEGY

The Covid-19 pandemic has had – and is still having – a terrible human cost. Many are facing fears for their lives and livelihoods, and for those of their families and friends. At such a time, looking at your investment strategy seems trivial. But once we’ve each dealt with the outbreak’s most pressing concerns, we do need to think about how it will change the shape of our investments in the future.

Around the world, share prices are in bear-market territory. This means they have dropped more than 20% from an earlier high point. But in every bear market, there comes a time when shares and other so-called ‘risk assets’ start to look very cheap. This is the point at which brave long-term investors start to buy them again. When this happens, markets find their bottom and investors can be richly rewarded as prices rise once again.

Knowing when and how to buy comes with difficulties, though. How can we be sure that share prices have tumbled all the way to the bottom? Is there a way to help us make the decision?

About strategic asset allocation

Strategic asset allocation (SAA) is about giving us a structured framework to help make these difficult choices. When times are good, investors relaxed and risk assets are expensive, SAA tells us to reduce exposure to risk. When the opposite is true, SAA says we should take on more risk.

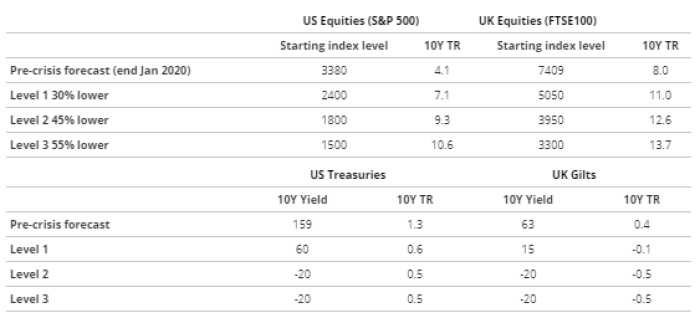

Our estimates of long-term returns for various asset classes drive the SAA process. The table below shows our provisional estimates for UK and US equities and government bonds. Since markets are so volatile, we have taken an unusual step, predicting outcomes based on several different possible starting price levels. It is likely that we will revise our forecasts several times this year as things become clearer.

Selected asset classes 10 year total return at various starting price levels, local currency % pa

*Once government bond yields hit zero, they can’t fall much further. That’s why levels 2 and 3 are the same.

The table shows estimates for annualised expected returns (in percentage terms) at equity prices roughly 30%, 45% and 55% lower than end-January 2020. The index levels represent the performance of a basket of large market-capitalisation equity securities and the relevant ICE Bank of America sovereign bond indices (comprising bonds of various maturities). We have selected the 10-year maturity government bond yield levels (in basis points) to roughly match. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future results and there can be no guarantee that these will be achieved.

At the moment, equities outside the US look cheap compared to the past. For US shares, the value for money is less obvious.

In our pre-Covid-19 forecast, the gap between equities and government bonds was quite small, suggesting a fairly modest reward for taking equity risk. At that point, our SAA suggested a cautious portfolio with less exposure to equities and more to emerging market sovereign bonds and US corporate bonds. Now, the gap is very large, so adding more weight to equities is more worthwhile for long-term investors. But this decision is not an easy one. We must be able to answer some important questions before we make the move.

How bad will the economic damage be?

Two factors will determine the extent of the damage from the coronavirus crisis. The first is the duration of the lockdowns that governments have put in place. The second is how well fiscal and monetary policy act to counter the economic damage they are doing.

Lockdowns are having immediate, and severe, effects on economies. We don’t yet know how long they will last. While events in China and South Korea offer some hope, it is uncertain whether the measures taken by Western countries will be as effective.

On the other hand, the extraordinary measures governments and central banks are taking should help to reduce the economic cost. These include large injections of cash to support incomes and moves to slash interest rates. While these actions are certainly helping materially, they will not be able to stop large-scale business failures and job losses.

As a result, our economists’ latest forecast is for global gross domestic product (GDP) to shrink by 8% in 2020. This is much worse than what happened in the global financial crisis (GFC). On the other hand, they think it is likely that we will see a very large rebound in GDP. They expect this to start towards the end of this year, eventually making up for most, but not all, of the losses. Of course there are huge uncertainties in this forecast, in both directions.

In the equity market forecasts shown in the table, we have assumed that the permanent loss of capital will be at a similar level to that caused by the GFC. But even with these fairly severe assumptions, the long-term rebound more than offsets the initial damage to share values.

What if the recession were to turn into a deep and lengthy slump? In that case, gains for investors would be smaller and the point at which they should buy equities would move further into the future. But investors receive a reward in return for taking on the higher risk (compared to owning government bonds) of holding equities. This ‘risk premia’ should still be attractive.

How would a regime shift affect investors?

Three things have remained very low since the GFC: interest rates, demand levels and inflation. But the shock caused by the global pandemic together with the fiscal and monetary policy response may be so profound that it changes the investment ‘regime’.

A shift could go one of two ways. On one hand, long lockdowns and weak policy responses could cause demand to fall further, leading to a deflationary slump. In such an environment, government bonds become more appealing. Low growth means that equities do poorly, but with deflation, government bonds become more valuable in real terms.

On the other hand, unprecedented fiscal policy could combine with massive central bank action to push inflation much higher. Such an environment tends to be positive for equities which can keep pace with inflation, but fixed income assets would lose value in real terms. After 50 years of mixing equities with government bonds in their portfolios, investors would need to look for alternative ways to diversify their holdings. These might include precious metals, commodities and real assets like infrastructure.

On balance, we think that once this crisis is over, we will most likely return to the current situation of low interest rates and low inflation. The caveat is that the risk of either of the outcomes noted above – deflation or high inflation – is now much higher. We'll know more as the crisis progresses, but it’s likely that a nimble approach to SAA will be needed.

What about timing?

As shown in our table above, the opportunity for investors is large, and is largest for non-US equities. A recovery from the current recession, propelled by unprecedented amounts of stimulus, could well result in annual equity returns of 20-30% over the first two years.

The sensible approach for a long-term investor is to gradually shift their risk profile from cautious to risk-taking. A gradual shift means they can ‘average’ back into the equity market. This reduces the risk of buying too soon or too late.

A good point of entry may be when numbers of Covid intensive care cases stop rising in the US. It won’t be the end of the crisis, but the tide will have started to turn. We’ll also have a better sense of the economic damage done, the scope for ongoing containment and the speed of recovery.

For more insights please visit aberdeenstandard.nl.