BNY Mellon: The Fed & Market Volatility

BNY Mellon: The Fed & Market Volatility

By Simon Derrick, Chief Currency Strategist, BNY Mellon

- Little question shifts in Fed balance sheet have coincided with trends in markets over past decade

- The Fed has appeared aware of this in the past

- It is hard to say whether turbulence was a result of Fed action per se

The President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Eric Rosengren, stated earlier this week: “Some have suggested that the Fed's balance sheet is partly responsible for financial market volatility at the end of 2018, but I disagree. The Federal Reserve's balance sheet decline has been quite gradual, and proceeded along roughly the same path when stock prices have been rising, as when stock prices have been falling."

Given the performance of markets since the start of 2018 it’s worth exploring this a little further.

While it’s difficult to definitively prove or disprove the proposition, what is easy to say is that turbulence in US equities began to emerge in February of last year and that this came just a matter of months after the FOMC initiated its policy of balance sheet reduction.

Moreover, while it’s true that the pace of balance sheet declines was steady, and that it never built to levels that mirrored the rate of balance sheet growth during QE3, it still seems odd to entirely disassociate the price action seen in US equity markets between September and January with what the Fed was doing, particularly given what had happened over the previous decade.

While the causal links can be disputed, what can’t really be argued with is that the announcement on March 18, 2009 by the Fed that it was picking up the pace of quantitative easing pretty well coincided with the start of the bull market in equities that has dominated for the past decade.

Expectations about the start of QE2 (from the summer of 2010) marked the start of the second leg of the rally, while the start of QE3 coincided with the earliest stages of the strongest leg of the bull market.

Equally, it was noticeable that the brief pauses in balance sheet growth in the spring of 2010 and spring 2012 also coincided with periods of market turbulence.

It’s also worth recalling the comment that then President of the Dallas Fed, Richard Fisher made to the FT as the taper tantrum emerged in 2013. He argued that bubbles had developed in a number of financial markets, specifically mentioning emerging markets and real estate investment trusts. He added: “I think these (market movements) are things that are noteworthy. I was mentioning (them at last week’s meeting). I wasn’t alone in drawing attention to these factors.”

In other words he was probably aware that one direct impact of the “tapering” discussion would be that investors in emerging markets would start to re-price risk.

It’s also worth recalling that Mr Rosengren said in January that he had to “take financial market considerations into account” when forecasting the outlook for the economy (and, therefore, the path for monetary policy).

While that’s not quite the equivalent of saying that the behavior of markets has been a function of what the Fed has done, it certainly sounds like a link of some kind was being drawn.

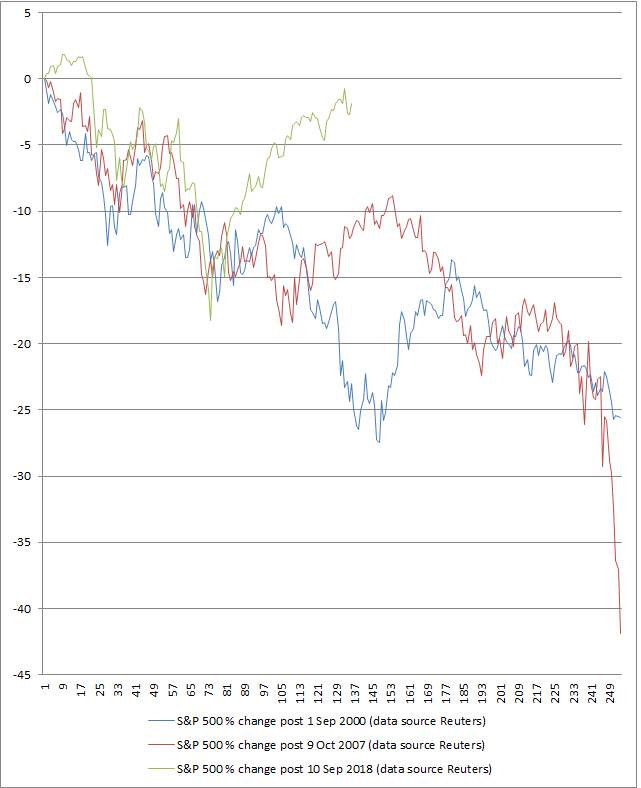

Does this ultimately matter? Perhaps not. What does matter, however, is what was revealed about the fragility of the market as the Fed took money out of the system, providing echoes of how it looked in both late 2000 and late 2008 (see chart). With odd bursts of volatility emerging in a number of markets (e.g. the TRY earlier this week) this might be worth bearing in mind.