Harry Geels: Why small businesses are in big trouble

Harry Geels: Why small businesses are in big trouble

This column was originally written in Dutch. This is an English translation.

By Harry Geels

The small-firm effect – that small companies do better on the stock market than large companies in the longer term – has not been visible for fifteen years. This is not surprising, since 'small caps' have to compete against five negative social trends. But there is a way out.

At the end of last year, the World Economic Forum (WEF) published a report titled ‘Small Business, Big Problem’ and subtitled 'New Report Says 67% of SMEs Worldwide Are Fighting for Survival'. This report provides the results of both a quantitative and a qualitative analysis. The Financial Times (FT) also wrote an article last week with the telling headline: ‘Are small businesses in big trouble?’ The answer to this question was a cautious 'yes', because smaller companies have to (re)finance significantly more expensively, partly due to the increased interest rates.

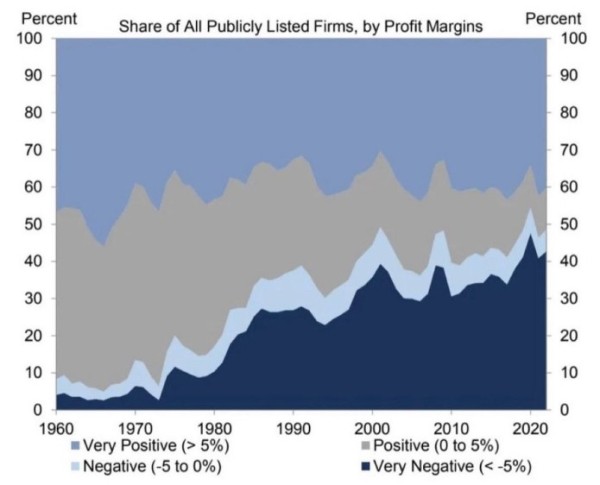

The WEF analysis had a long-term character, while the FT mainly pointed to the short-term problem of increased interest rates. However, we can broaden the analysis even further by looking at five key long-term social trends that are putting small businesses at a disadvantage versus large ones. The fact that a relatively large number of companies are not doing well can be seen in Figure 1. Only 54% of companies are still profitable! The important message is that the profitability percentage has been structurally declining since the early 1970s. There are five causes.

Figure 1: The number of American companies that are profitable has been decreasing for years

Source: Goldman Sachs, 8 October 2023

1) Small businesses have less easy access to (cheap) credit

The first major problem is caused by banking disintermediation. The ever-growing banks are actually doing more and more business with the large companies, partly through regulation, partly through efficiency (each loan always costs a minimum amount of compliance and paperwork). Small companies therefore more often resort to private markets. This increases financing costs, because the sourcing challenges and complexity increase. Large companies can finance themselves more cheaply and easily through banks and the stock exchange.

2) The power of the oligopolies

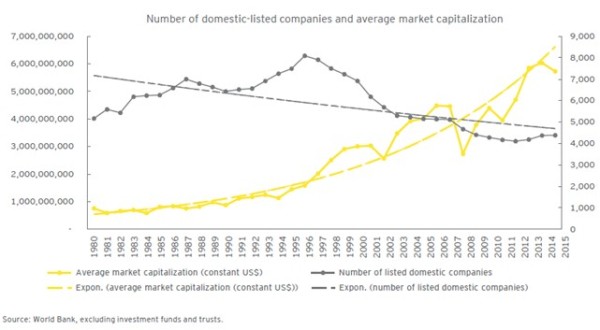

More and more industries in more and more countries are dominated by oligopolies. Certain sectors are even ruled by the ‘winner takes all’ syndrome. Figure 2 shows that the number of listed companies has actually been decreasing since the late 1990s and that the average market value of companies on the stock exchange shows a clear upward trend. This is a bad development from a social perspective, because oligopolies create barriers to entry for smaller companies. As an aside, oligopolies are on average less good for consumers, innovation and economic growth.

Figure 2: Number of listed companies and their average market value

Via The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

3) Passive investing

The third social trend is the increase in passive investing through index funds and ETFs. More and more investors, especially within (private) pension solutions, invest passively because of perceived benefits such as transparency and lower costs. The problem is that this means that more and more 'automatic' money flows to the largest companies, because most passive investment products weigh the underlying investments based on market value. Investments with less liquidity are less suitable for passive solutions because continuous trading is complex.

4) Regulation ('too small to comply')

Increasingly strict laws and regulations are a fourth complication for small businesses. Complying with all the rules is becoming increasingly difficult and expensive. We see this in all kinds of areas, for example in the field of sustainability. Small companies may have a sustainable revenue model in themselves, but they often do not have the people to provide all data points to, or complete questionnaires for, the data vendors. By the way, this creates a size bias in the ESG scores: large companies have more opportunities to improve them.

5) Increasing effort to attract 'high potentials'

Finally, the labor market. Small companies are less able to attract and retain 'high potentials', as also stated in the WEF report. Large companies have a 'higher' salary structure, more career opportunities and also more opportunities to offer their staff all kinds of (personal) development programs, more flexible working hours and working environments than small companies. Younger generations in particular find these types of secondary employment conditions, which small companies are less likely to be able to offer due to their nature, important.

The way out

The 'small business problem' is not easily solved. The solution starts with a good analysis of the problems. Part of the solution lies with politics. Thinking lines are: spliting up big business (for example never more than 10% of a certain market), abolishing the lobby circuit, abolishing (tax) benefits and subsidies for large companies, and stopping the legalization and bureaucratization of society. For example, fire half of the government policy officers.

There are two points of attention when it comes to investing. Firstly, investors could invest in 'private markets', outside the stock exchange. This way they help small businesses get the financing they need. Secondly, investors should be careful when choosing passive investing. This is a political statement, as it benefits big businesses. It may be good for investment returns (because of the lower costs), but not such a good idea for society in the long term.

And then, finally, there is something special. As mentioned, the relative number of profitable companies has been declining since the early 1970s (see Figure 1). To be more precise, over the period 1971-1973 the Bretton Woods monetary system was dismantled and a system of free exchange rates emerged, with central banks later pursuing an (increasingly looser) inflation policy. Is this merely a (coincidental) correlation or a causal relationship? Maybe more about that next time (suggestions for an answer recommended).

This article contains a personal opinion from Harry Geels