Schroders’ Keith Wade: Coronavirus veroorzaakt zeer ernstige wereldwijde recessie

Schroders’ Keith Wade: Coronavirus veroorzaakt zeer ernstige wereldwijde recessie

Schroders heeft in zijn vooruitzichten voor de wereldeconomie de impact van het coronavirus verwerkt. Het resultaat is niet goed. Volgens Keith Wade, hoofdeconoom van Schroders, wordt 2020 het slechtste economische jaar sinds de jaren dertig:

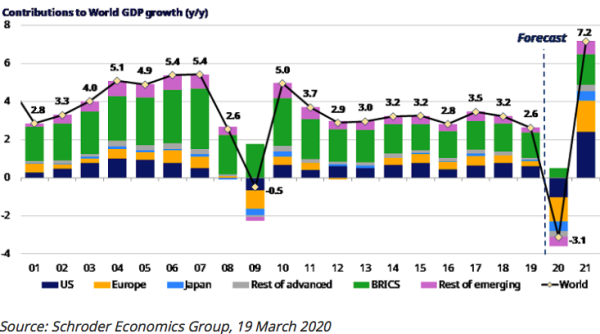

The coronavirus is having a severe effect on global economic activity and amidst considerable uncertainty we have attempted to gauge the impact and updated our forecasts. We now expect to see the world economy contract this year by 3.5%, before rebounding by 7.2% in 2021. The forecast incorporates a severe recession in the first half of the year which, even with a rebound in the second half, means 2020 is set to be the worst year for activity since the 1930s.

Although there is considerable support from central banks and governments, the dramatic downturn reflects the effect of shutting down large parts of the economy as the authorities attempt to suppress the virus. An indication of the magnitudes can already be seen in the latest data from China, where we saw falls of 20% in retail sales and 25% in fixed capital investment during the period when much of the economy was in lockdown.

These figures are consistent with the high frequency data and our China activity indicator says that the economy contracted during the first quarter. The official numbers may tell a different story, but these figures give an indication of what to expect elsewhere.

Severe contraction in global economic activity expected

Thankfully the number of new Covid-19 cases in China has levelled out, but we are at an earlier point on the curve in Europe and the US. Our underlying assumption is that these regions go through a similar process of locking down and restricting population movements so as to suppress the spread of the virus. This results in a significant hit to activity in Q2 in the US and Europe with falls in GDP of between 10 and 20% (not annualized). Such outcomes have rarely been seen in the post war economies where normal fluctuations in GDP are between 1% and 2%.

Policymakers to the rescue?

We have factored in the recent moves in monetary and fiscal policy around the world and expectations of more to come. We see these as a safety net to cushion the economy and limit the damage from the fall. It is vital that the financial system continues to provide liquidity to firms and households so they can withstand the impact of the collapse in activity on cash flow. Otherwise a temporary hit will cause permanent damage to the supply side of the economy. If we see a widespread collapse of business there will be little left to support the recovery.

In this respect, lower interest rates are less important than measures to ensure banks have the confidence to lend rather than foreclose on borrowers, and liquidity continues in commercial paper and credit markets. The Bank of England’s actions combined with government guarantees on loans and measures to ease cash flow such as the suspension of business rates all help in the UK.

More widespread use of fiscal policy, such as the Trump plan to give lower and middle income households $1000 each, would also be helpful to support consumption in the face of the inevitable increase in unemployment.

We would expect the measures taken to contain infection to be effective in the US and Europe and alongside a seasonal fall back in the virus during the northern summer, the economy should experience a strong rebound as people go back to work in the third quarter. The policy bazooka will then be fully felt as low interest rates, tax cuts and increased government spending continue. Going into 2021 we would expect a modest tightening of monetary policy around the world as the global economy booms.

Risks remain

Coronavirus returns?

Making forecasts in this environment is particularly uncertain as we are having to anticipate the evolution of a virus. As has been made clear in recent work by Warwick McKibbin and Roshen Fernando at the National Bureau of Economic Research, there are a number of different scenarios which could play out with the number of deaths ranging up to 68 million depending on the spread of the virus. Analysis from our Data Insights Unit also shows how different reinfection rates can create very different outcomes.

More immediately, the risk is that the virus returns after the restrictions are lifted. The UK government’s original strategy was to prevent such an outcome by allowing the virus to spread and create a “herd immunity” in the population. Given the risks around that policy it has now been dropped and the UK is following the rest of Europe in closing schools and restricting movement.The cost though is that the risk of the virus returning is greater and consequently the world economy faces the prospect of having to go back into quarantine later in the year. The consequence would be another recession – a double dip in activity. A similar outcome would occur if we did not see a seasonal drop off in infection rates.

Euro crisis 2

The second risk is that the crisis exposes the underlying weaknesses in the world economy. As Warren Buffett said – you only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out. This may sound pessimistic given the promises to do whatever it takes, but sharp falls in economic activity do expose weaknesses as we saw only too clearly after the global financial crisis.

In the UK a number of weaker corporates have already gone out of business. More worrying would be a return of a crisis in the eurozone, where the worst hit economy, Italy, also has the most precarious finances.

There will be significant breaches of deficits and it is difficult to see any appetite for the sort of austerity measures which were imposed by the EU after the last crisis. The recession will be a considerable challenge for the eurozone, especially if it is prolonged.