Natixis IM: Higher energy prices have less impact than people think

Natixis IM: Higher energy prices have less impact than people think

By Jack Janasiewicz, CFA, Portfolio Manager and Portfolio Strategist, Natixis Investment Managers Solutions

Oil prices, as measured by West Texas Intermediate crude (WTI) have recovered from a COVID induced low of $32 a barrel to almost $80 per barrel. More recently, the 27% surge since mid-August has raised some concerns. Will this recent spike begin to act as a headwind for the markets? Should investors take note?

A few things to ponder regarding the surge in oil. The impact to markets can come via three channels: higher inflation, less disposable income and pinched profit margins. On the inflation front, it’s important to distinguish between demand vs supply driven impulses. Demand driven impulses can be directly addressed through monetary policy administered by central banks. The economy is running hot. Demand is driving up the need for oil and thus pushing prices higher. Hike interest rates and cool off demand.

Pretty straight forward. But in this case, we are seeing more of a supply disruptions driving up prices. COVID related issues have crimped the workforce that is required to help bring oil to the market. Couple this with a lack of investment resulting from regulation and the shift to ESG and we simply have not been keeping pace on the capex and production side of the equation. These issues all fall under supply constraint related worries and ones that are not easily addressed through a monetary policy response and interest rate hikes.

In an economy like the US where consumption accounts for close to 70% of GDP, the hit to the consumer’s wallet could very easily begin to dent retail sales. With the typical consumer spending more money on gas and less on apparel and restaurants, it’s easy to see how a knock on effect from slowing consumption could hurt the prospects for growth and earnings. But this logic needs some updating as today’s energy backdrop is not the same as your Mom and Dad’s.

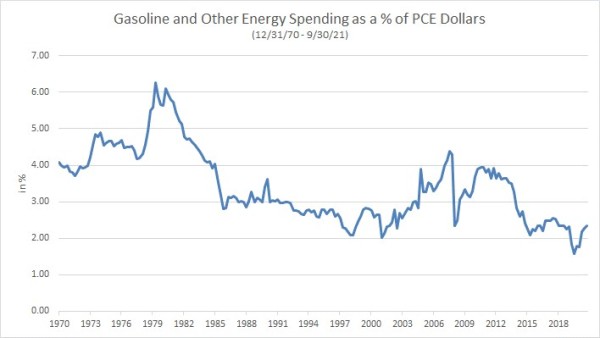

Why? Here in the US for example, we are simply spending less on energy and energy related goods. Spending on gasoline and other energy related goods for example has fallen to just 2.35% of total spending. This is down from the 6+% that we saw back in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Source: Bloomberg, US Energy Information Administration.

Gasoline and energy related spending is simply becoming a smaller portion of our consumption basket these days. But prices at the pump do matter. Why? Because they strongly influence inflation expectations. Consumers do take note of how much they spend each week to fill their cars along with how much they pay for their groceries.

So while we may be spending less on filling up our tanks each week relative to our total spending, we are making mental notes of the change. And these changes filter into our expectations for future price levels. Inflation expectations are strongly tied to these two inputs so it does bear watching. Should inflation expectations become unhinged as a result, then policy makers will have a challenge on their hands and these expectations tend to bleed into the broader real economy.

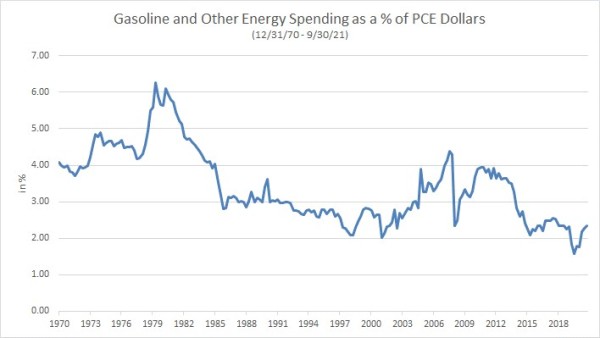

Energy intensity is defined as the amount of energy used to produce a given level of output. Energy intensity as a whole has been steadily declining for years as well. As economies continue to advance and upgrade, economic efficiencies begin to take hold as well as the shift towards alternative energy sources.

The chart below reflects this shift as the US economy continues to use less and less energy for each unit of output as measured by real GDP.

Source: Bloomberg. US Energy Information Administration.

The important point here: we simply are less exposed to higher energy prices because global economies have learned to do more with less.

Lastly, higher energy prices could easily begin to erode profit margins. With input costs on the rise, and some of this being driven by stronger energy costs, the issue as to who ends up absorbing these higher costs remains critical.

Companies can opt to pass along these higher input costs to their consumers but this leaves them at risk of consumers going elsewhere in search of lower prices or different products altogether. Should companies choose to absorb these higher costs, the resulting margin compression will see a hit to their bottom line. As earnings soften up on the back of this, stock prices are likely to follow suit.

We note that these impacts are on an case by case basis and we have seen an impressive improvement in profit margins post COVID as companies learned to do more with less during the pandemic. These efficiency gains accrued during this time are here to stay, leaving some capacity for firms to absorb higher costs without facing a significant pinch to their operating leverage gains relative to pre-COVID levels.

To summarize, energy intensity has dropped markedly over the years. And the consumer is spending less and less of his disposable income on filling up his car. These gains have changed the playbook for higher energy prices. The framework for analyzing the impacts on the economy from higher energy prices needs to be updated. This isn’t your Mom and Dad’s energy concerns. Higher oil prices likely will have less an impact than many believe.